Slate is producing a new series that focuses on technology and incarceration. You can follow the series–Time, Online–at

Category: Access

Censorship is common in prisons–from blanket bans on vendors to specific titles. In preparation for Prison Banned Book Weeks (which begins today!), colleagues and I discussed the realities of censorship inside. You can view the recorded training on censorship in carceral settings by registering at

https://www.everylibraryinstitute.org/censorship_in_carceral_settings.

Interested in joining the campaign against pervasive book bans inside? PEN America has released a new report and toolkit for raising awareness of these practices and engaging in advocacy. Their report and action steps are located at

https://pen.org/campaign/prison-banned-books-week-2023/.

The toolkit for a Banned Books Week social media campaign is at

https://pen.org/prison-banned-books-week-toolkit/.

Want to see what books are banned in prisons in your state? The Marshall Project is continuing to collect this information and to make it publicly available at

https://www.themarshallproject.org/2022/12/21/prison-banned-books-list-find-your-state.

As part of San Francisco Public Library’s “Expanding Information Access for Incarcerated People” grant project, we have recently released a white paper titled “Technology in Carceral Facilities: Trends, Limitations, and Opportunities for Libraries.”

This white paper covers relevant literature published from January 2020 to December 2022. It glosses emerging and continuing trends in the use of technology in carceral facilities. It provides an overview of trends in recent publications in library and information science and similar fields about how technologies inside shape people’s experiences of incarceration and reentry. It closes by highlighting work by libraries that may indicate possibilities for supporting incarcerated people and people in reentry through making library services and programs that utilize technology available within facilities, and by offering some examples of how libraries can support patron’s digital literacy development after they are released.

The white paper is freely available online at

“Technology in Carceral Facilities: Trends, Limitations, and Opportunities for Libraries.”

or through the grant page at

ITHAKA S+R has released a report that brings together and analyses the content restrictions and media review practices of prison systems in the United States. The post announcing the report highlights that:

- Key terms and language are common across DOC censorship policies. Despite strong similarities in language and framing, however, the policies and procedures related to common terms differ greatly across states.

- Forty-two of 51 media review directives limit the vendors from which materials can be purchased. This type of “content-neutral” restriction limits the availability of information and may increase costs and logistical burdens on higher education in prison programs, students, and autodidactic learners.

- Forty-four of 51 media review directives have clauses addressing and limiting access to sexually explicit or obscene content. The reasons for this are historically complicated, but these policies are currently intended to maintain an environment free of sexual harassment. In some cases, however, these policies explicitly target LGBTQ+ content. Such policies can affect access to educational materials from art history and biology to contemporary queer literature.

- The legal power of DOC to surveil and censor is grounded in the protection of “security, good order, or discipline.” In practice, the term frequently serves as a catchall, providing broad latitude to censor media. This covers a startling amount of ground, justifying everything from banning books on community organizing or union history, to prohibiting access to fantasy novels that have maps of fictional lands.

- Content protection clauses or carve outs exist and primarily allow access to educational or culturally significant content. While such provisions ostensibly allow access to publications that might otherwise be censored, the way these policies are framed often narrowly limits application.

- Publication review and censorship appeals processes are addressed to some extent in nearly all policies. However, appeals processes often inequitably burden people who are incarcerated and the programs that seek to serve them.

The full report includes a media review policy that can be used to craft a more transparent and less arbitrary review process for materials.

Interested in learning more about banned books inside of prisons? The Marshall Project has recently released a new tool for viewing banned books lists by state.

I am guest editor on a forthcoming issue of the Journal of Intellectual Freedom & Privacy on the topic of carceral systems and censorship. Look out for the issue later this year!

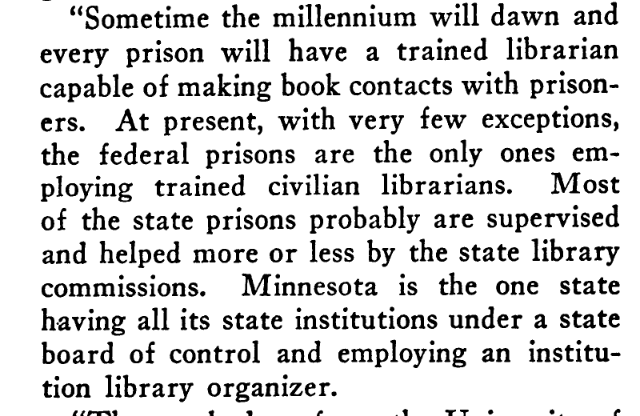

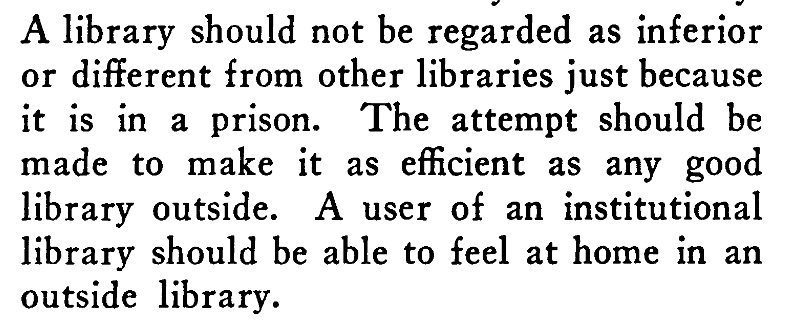

The 1982 Library Services in Federal Prisons survey is a treasure trove! (This survey was conducted by the Federal Prisons Committee of the Library Services to Prisoners Section of the American Library Association.) In addition to an analysis of contemporaneous library services in federal prisons, it includes a comprehensive history of library services in federal prisons. That history led me to these 1933 passages–

…

Excerpted from Jones, E. K. (1933). Institution Libraries Round Table. Bulletin of the American Library Association, 27(13), 706–715.

These types of discoveries help me to position my own work within the larger, often difficult to locate, scope of library services for people who are incarcerated. They also attest to the great need for more services. The new millennium imagined in 1933 has not yet arrived.

Despite this, there is a renewed energy within the profession and among LIS students for attention to library services for people who have been incarcerated. Change may still be on the horizon.

Many thanks to the American Library Association Archives for making this research possible.